A few days ago I watched Takeshi Miike’s Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai (2011). This is Miike’s second collaboration with English producer Jeremy Thomas, following 2010’s 13 Assassins. Both films are jidaigeki, and both are remakes of black and white Japanese films from the 1960s

A few days ago I watched Takeshi Miike’s Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai (2011). This is Miike’s second collaboration with English producer Jeremy Thomas, following 2010’s 13 Assassins. Both films are jidaigeki, and both are remakes of black and white Japanese films from the 1960s

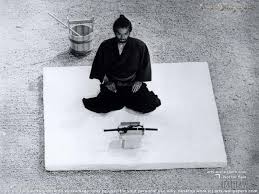

Eiichi Kudo’s The Thirteen Assassins (1963) is an obscure (but by all accounts decent) story of 13 samurai who band together in order to assassinate a sadistic nobleman whose cruelty threatens the stability of the Tokugawa shogunate. Both Kudo’s and Miike’s versions are pulpy action films in the mode of Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967), and Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954). Miike uses Kudo’s template as a showcase for his own brand of violent action. The film’s set up is essentially an excuse for a 50 minute climactic battle in a booby trapped village. In this part of the film the narrative recedes into the background whilst the the “cinema of attractions” of the action spectacle takes over. The village is a haunted house ride (a different surprise around every corner) within which Miike blocks out time by combining rapid cut chaotic fighting scenes against graceful balletic movements captured with longer kinetic camera movements. Violence is mainly implied, leading up to coup de grace moments of explicit gore which mark the end of sub-scenes (within this long uberscene). The generic template of Kudo’s original allows Miike to explore his various styles of action film making over an extended period. In my opinion this is enough of a departure from the original film to justify the remake. Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai is a different matter. This film is based on Masaki Kobayashi’s 1962 film Harakiri. Harakiri is an undisputed classic, and arguably Kobayashi’s masterpiece (it must contend with the beguiling Kwaiden (1964), and the monumental Human Condition trilogy (1959-1961)). This is not to say that remakes cannot co-exist peacefully with their originals, 13 Assassins is a good example. Both versions of The Ballad of Narayama (Keisuke Kinoshita in 1958 and Shohei Immamura in 1983) are superb. Both are adaptations of a book by Shichiro Fukazawa which complicates the line of descent. Similarly the Coen brothers claim that their film True Grit (2010) is a new adaptation of Charles Portis’ book rather than a remake of Henry Hathaway’s 1969 version (a solid John Wayne western which the Coens embellish by drawing out the themes of Protestantism with the aid of Carter Burwell’s score). Harakiri’s is an original screenplay. This means that Miike’s version has no point of origin except for Kobayashi’s film. As the setting is the same, Miike cannot utilise the disconnect of place or language that allows films such as Yojimbo (1961) and A Fistful of Dollars (1964) to stand apart (although both films are inspired by Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest). Miike follows the structure of the original so doggedly that the audience is compelled to compare the two films. The 1962 film concerns a ronin, Hanshiro (Tatsuya Nakadai in one of his signature roles), who arrives at the palace of a powerful clan and requests use of the courtyard to commit seppuku. Hanshiro is told by the clan counsellor of other samurai who have been appearing at the residences of noblemen requesting a place to kill themselves with honour. Such “suicide bluffs” are undertaken with the hope of receiving employment or handouts. An example was made by calling the bluff of a young samurai, Motome, so lacking in honour that he had sold his swords and replaced them with wooden blades. Motome was forced to commit an agonising seppuku using his inadequate replacement dagger. Hanshiro explains via flashback that Motome was the husband of his only daughter, and the father of his grandchild. Following the disbandment of Hanshiro’s clan, and a period of peace, there was no work for soldiers such as Hanshiro and Motome. Barely scraping by in poverty, an illness to Motome’s wife forces him to sell his swords to buy medicine. When their son also falls seriously ill, left with nothing to pawn, Motome is compelled to try a “suicide bluff”. With the counsellor steadfastly unsympathetic to Motome’s fate, Hanshiro reveals that he has tracked down the clan’s three most accomplished swordsmen and bested them in single combat. Rather than killing them he cut of each’s topknot is a mark of shame. By now embarrassed and enraged, the counsellor orders his soldiers to cut down Hanshiro. Tanshiro holds off the clan, killing several. Eventually he demolishes a suit of ornate armour that represents the martial legacy and honour of the clan. Hanshiro is only stopped when three riflemen appear and gun him down. The most striking themes of the film are utter contempt for the Bushido code and the notion of “honourable death”. It no great leap to suggest that Kobayashi extends these criticisms to Japanese militarism and imperialism in the 20th century. Miike’s remake has the same plot, but with some changes. Rather than have Hanshiro seek out and defeat the clan swordsmen one by one, Miike has him engage them all in three-on-one combat. Whilst this allows for a Yojimbo type fantasy fight moment (Miike shoots this scene like a side scrolling beat-em-up), it sacrifices the slow piecing together of Hanshiro’s tale. In the original Nakadai’s monotonous refrain of “one more thing”, before each reveal, hammers in each shameful twist for the clan counsellor. Hanshiro’s ponderous deliberations over his story reveal a sadistic tendency to draw out the suffering of his foe, and a relish of his power as storyteller. Miike relinquishes this for the sake of action. In the climatic fight Miike continues his characterisation of a Hanshiro more passive than the original character. In a neat twist Hanshiro unsheaths his katana to reveal a wooden blade. He cannot seriously wound his attackers, only stave them off until inevitable death. Rather than destroy the ceremonial armour himself, Hanshiro throws an attacker into it. Once again the statement of purpose seems muted. Miike’s strangest decision is to omit Hanshiro’s death by firing squad, the clearest example of the senselessness of the Bushido code. You start to question whether Miike is as committed to this ideology as Kobayashi was. Miike’s one major coup is in his casting. Nakadai’s performance in the original film is a masterclass in restraint and gradual revelation. His voice is deep and declamatory. Miike cast renowned Kabuki actor Ichikawa Ebizo XI in the role of Hanshiro. Ebizo’s theatrical vocal projections rival those of Nakadai’s. And whilst Nakadai’s face is etched with grief, Ebizo has an unblinking, eye-popping stare that hints at inner madness. I can only assume that this facial expression of his is very well known in Japan.

In other technical aspects Miike simply can’t compete. His film is in colour (3D in fact, although I watched it in 2D), but the tones are oddly murky. Only the opening shot of the crimson wood of the palace, and a later pillow shot of maple leaves in autumn, take advantage of the colour palette. Kobayashi’s film has a very strong visual identity forged by two reoccurring shots in the courtyard scenes. One is a fixed over-the-shoulder shot from behind the counsellor looking down at Hanshiro. The other is a fixed over-the-shoulder shot from behind Hanshiro looking up at the counsellor. These shots quickly establish the power relations in the film, and anchor the film between the various flashbacks. Miike prefers to keep his camera mobile, constantly circling Hanshiro. This gives us a sense of the forces that surround him, bit isn’t as effective as Kobayashi’s static camera.

Soundtrack duties for Miike’s film are provided by superstar composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Whilst I admire Sakamoto’s work with Nagisa Oshima (Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence (1983) and Gohatto (1999)), this soundtrack has too much melodramatic swelling strings for my liking. Far superior are the disconcerting twangs and shimmering gongs of the original film’s soundtrack. This was written by the innovative and influential experimental composer Toru Takemitsu. Amongst his other impressive body of film work are soundtracks for Kurosawa’s Ran (1985), Kobayashi’s Kwaiden, and best of all: Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Woman in the Dunes (1964).

One would expect Miike to deliver action scenes to compete with Kobayashi (if 13 Assassins is any benchmark). However, the suicide by wooden dagger is far more visceral and gut-wrenching in the original. Hanshiro’s showdown with the swordsmen is an exciting piece of video game inspired filmmaking, but can’t touch Kobayshi’s expressionist duels. Hanshiro’s third duel takes place on a windswept hill with broiling gothic clouds in the sky. The combatants are presented in oblique angle close-ups, before the tense and brief fight.The final fight in the palace is satisfying and well filmed in both cases. In both films the scene is long and flowing. Kobayashi manages an average shot length of 17 seconds and Miike 22 seconds. Miike also manages to insert some absurdist humour: a brief shot of a cat, completely unfazed by the battle raging around it. However, Kobayashi wins the points for sticking to his guns (both literal and metaphorical).

Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai is well made, enjoyable, and was critically well received. However, being almost identical, and in almost every way inferior to its original template, there is little to justify its existence. Miike’s calling card has always been originality. When you can call a Miike film (whether you liked it or not) unoriginal, it seems a somewhat sad betrayal of this surreal and boundary pushing film maker’s sensibilities.